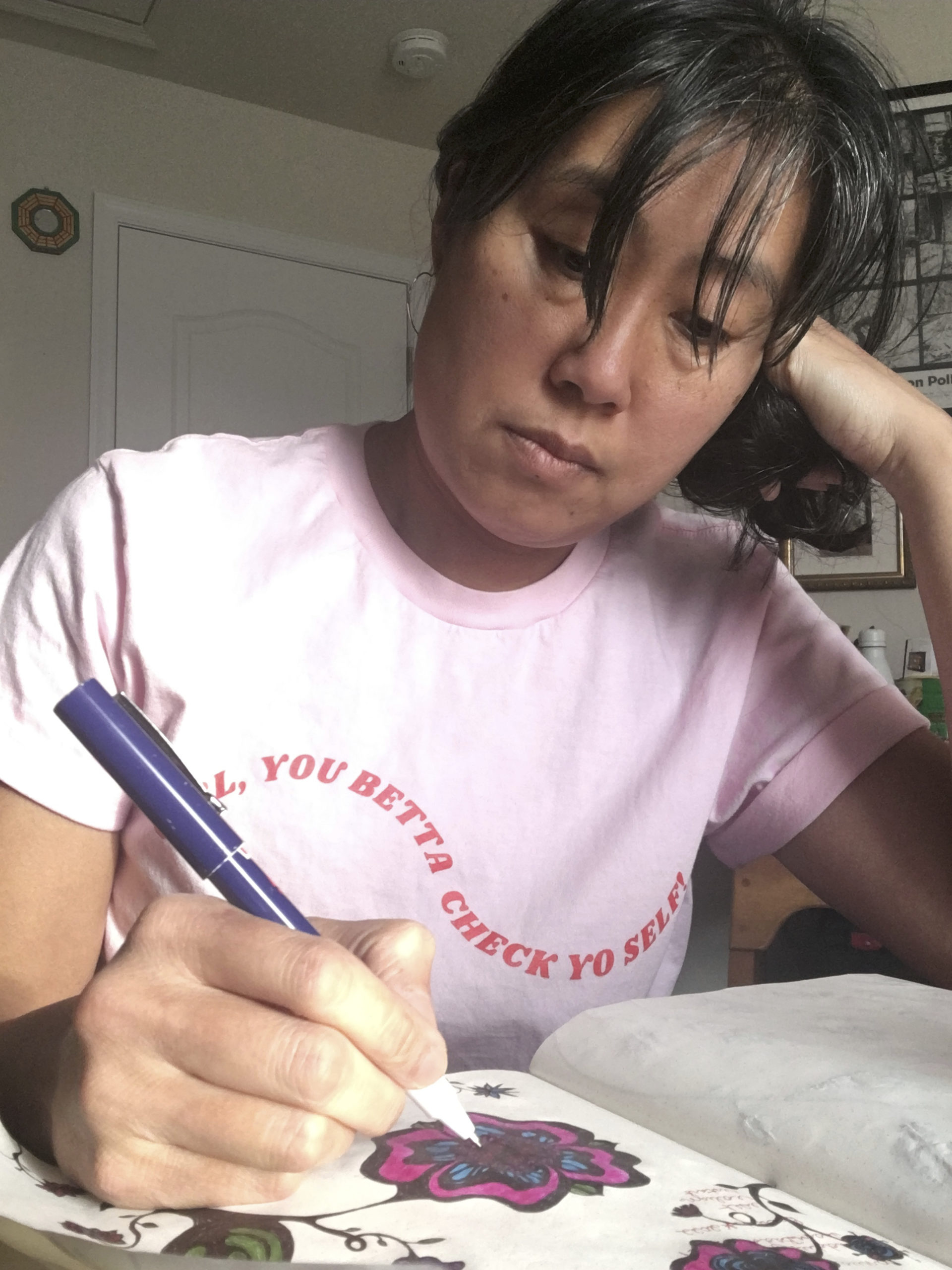

Healing body and emotions: Shangrong Lee

- 07/26/22

I wouldn't say I'm an extrovert now, but I'm more outgoing than I was before. Finding my voice is really sharing my experience with breast cancer and not being afraid to talk about it or feel shame for it.

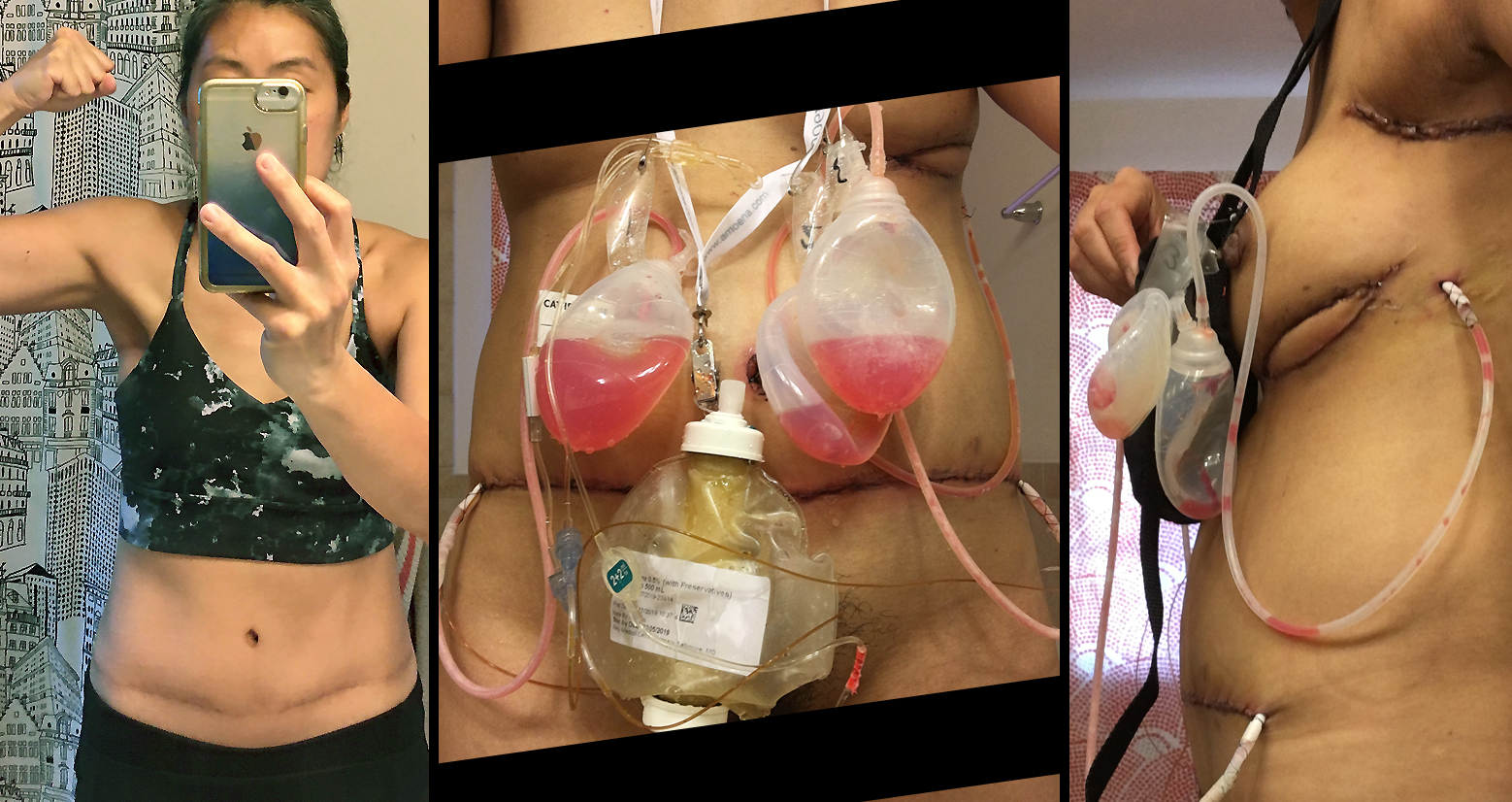

Warning: This post contains graphic images.

Years before she would have a mastectomy as part of breast cancer treatment, Shangrong Lee was a child living in Kansas, worried about her physical appearance.

While that’s a common concern for many young girls, it was particularly hard on Shangrong, a child of Taiwanese immigrants. Her family was one of the few families of color in the area, and she heard cruel racist comments about her body from other children.

“They would say, ‘Why is your face so flat? Did you get run over by a truck?’ Or because my eyes are slanted, they would ask, ‘How do you see through them?’” she recalls. They challenged her with questions about why her hair was black instead of blonde or brown and called her “flat as a pancake” for having small breasts.

“These were what children, my peers, would point out was different about me and that would just amplify my own insecurities,” Shangrong says.

Her parents, who were trying to assimilate in the majority white culture, didn’t know how to address the racial identity issues their daughter faced and the taunts she received about her body. They encouraged her to focus on working hard in school.

At age 40, Shangrong decided to take up running after having two children and gaining extra pounds she didn’t want. She thought running would help her lose weight, strengthen her body, and avoid developing diabetes, which ran in her father’s family. She also had been managing depression since her early 20s, when she was hospitalized briefly after a suicide attempt. Her treatments in the following years included talk therapy, art therapy, and antidepressant medicine. Running might help her mental health as well, she figured.

“I had never liked running when I tried it before, but something just changed this time,” she says. She used an app to guide her gradually between short amounts of walking and running until she was comfortable running three miles. Her pace was slow by elite running standards, but she was happy with the moderate time and distance she achieved.

Soon, though, running would become even more vital to her self-image and to her physical and emotional wellbeing.

Running and recovery

Around the time she started running, Shangrong’s primary care physician encouraged her to get her first mammogram. With a busy schedule and because she had no family history of breast cancer, she delayed doing that. In 2017, when she was 43, a volunteer teacher, and involved with her sons’ activities, she found a lump in her left breast while doing a routine breast self-exam in the shower. She was diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. Her Oncotype score was borderline, so she opted to do mastectomy and radiation but not chemotherapy.

“The day I was told, ‘You have breast cancer,’ I had flashbacks to my childhood” and being bullied by other children. “That experience made me feel ashamed and ugly,” says Shangrong. “At first, that is how I felt about my breast cancer diagnosis.”

Feeling shame was also “the natural way to think from my upbringing,” she says. “I didn’t want to be seen as a burden to others or look weak for getting breast cancer.”

She had a nipple-sparing single mastectomy, which helped her adjust to how she looked after surgery. The scar in her breast area didn’t concern her much, but she was bothered by the hip-to-hip scar on her abdomen from surgery that removed fat tissue for use in a DIEP flap breast reconstruction. It took time to get used to the physical sensations and emotional feelings she had from the abdominal scar. “I would look there, and it felt like a dotted line for breaking myself in half,” she says.

Shangrong calls running her “healing power,” especially during active treatment when her emotions went up and down. She credits exercise with releasing endorphins that helped her feel better afterwards. As she ran, listening to hip hop music, she focused on her breathing rather than on feeling depressed about her diagnosis or anxious about having a breast cancer recurrence. “It was my time alone,” she says. “That was my self-care.”

Through the trauma of treatment, she says, “I learned to appreciate my body and love it even though it betrayed me.” Once the abdominal incision healed and the stitches removed, she took a long look at the scar across her body.

“I was just amazed that I had gone through all this, and I was still standing, alive and breathing,” Shangrong says. “My mindset changed, and I was feeling comfortable in my own skin. That’s when I thought, ‘You know, I can run a marathon!’”

She trained to run the 2020 New York City Half Marathon before that race was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. She still ran the 13.1-mile distance on race day, but did it in Washington, D.C. She kept up her training and then competed in the 2021 New York City Marathon. For both events, she raised funds for the Breast Cancer Research Foundation in honor of her mother-in-law, who had died of metastatic breast cancer, and for people with metastatic disease who were unable to run. Now, Shangrong still runs but not long distances. She wants to run a marathon again when she has time for training.

Maintaining mental health, finding community

Although Shangrong felt depressed upon learning she had breast cancer, she says she did “surprisingly well” managing her mental health during treatment and afterwards. “When people talk about hitting rock bottom, they would say the cancer diagnosis was rock bottom. But for me it wasn’t,” she explains. “My rock bottom was when I was 23 and attempted suicide. The cancer diagnosis was a testament to how much I have overcome since my 20s.”

She was taking sertraline (Zoloft), an antidepressant, at the time of her breast cancer diagnosis. Her doctor switched her to venlafaxine (Effexor), another antidepressant, when she began tamoxifen treatment because venlafaxine does not affect tamoxifen’s function.

In addition to that medicine and running, she found other ways to support her mental health. Some were short-term: For five weeks during radiation treatment, to calm her nerves after each daily session, she stopped at a local shop for a toasted coconut donut and hazelnut coffee. Other methods have sustained her longer, such as yoga (which she started to help her running but discovered it benefitted her emotions as well), reading women’s breast cancer stories on Instagram, and journaling her own thoughts and experiences. She began writing to help her process what she had gone through.

“No one tells you that, after everything is done, you’re going to really deal with the mental health part. When you’re in active treatment, you just keep doing it like you’re sleepwalking through it. And then, when it all stops, it just hits you like a wall,” she says.

During her breast cancer experience, Shangrong’s husband was supportive of her, but her family of origin was not. She attributes that more to personality dynamics than to cultural influences. Her feelings of isolation were amplified by living in a small town, White Plains, Maryland.

Fortunately, she discovered helpful connections online, including another Taiwanese woman who was treated for breast cancer. Shangrong says Taiwanese people are often very private about personal information and feelings, and breast cancer is one of those “things you don’t talk about.” She was glad to find someone who came from the same cultural background as she did. “Knowing her helped me because she was talking about her breast cancer diagnosis out loud, without shame. It felt like I was given permission to take up space and talk out loud about my own diagnosis,” she says.

Shangrong found LBBC on Instagram and joined the Young Advocate Program in 2021. She learned what participating in advocacy means, the many ways to be an advocate, and how she can help others. She also connected with For the Breast of Us, a breast cancer community for women of color, and is now one of the group’s Baddie Ambassadors.

“LBBC and For the Breast of Us were my lifeline, helping me translate my trauma into purpose,” she says. “I make sure to be active where I can serve to represent people that look like me. Not just talking about my personal story, but also to find community.”

Along the way, she has gained a new self-confidence. “I wouldn’t say I’m an extrovert now, but I’m more outgoing than I was before. Finding my voice is really sharing my experience with breast cancer and not being afraid to talk about it or feel shame for it.”

This article was supported by the Grant or Cooperative Agreement Number 1 U58DP006672, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Stay Connected

Sign up to receive emotional support, medical insight, personal stories, and more, delivered to your inbox weekly.