From her experience to real-life help for others: Rosemary Carrera

- 10/21/22

Rosemary Carrera, of Coral Gables, Florida, had little time to spare when she went to see a new primary care doctor. She had recently finished maternity leave and had returned to her job as an optometrist but was bothered by pain and swelling in her hands.

The doctor ordered tests for Rosemary’s hand problems. As she was leaving his office, he said she also should schedule her first mammogram, since she had turned age 40 a few months before. When he gave that advice, “I swear he heard me roll my eyes,” Rosemary says. With caring for an eight-month-old baby and running a busy optometry practice with her brother-in-law, she didn’t need something else to juggle.

But the doctor urged her, saying she could have the mammogram at the same time as the other tests. Looking back now, Rosemary says if he hadn’t said that, she probably would have dismissed the idea. Instead, she took his advice and was tested. There was no problem in her hands. The mammogram, however, showed more serious findings. In August 2018, she was diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer.

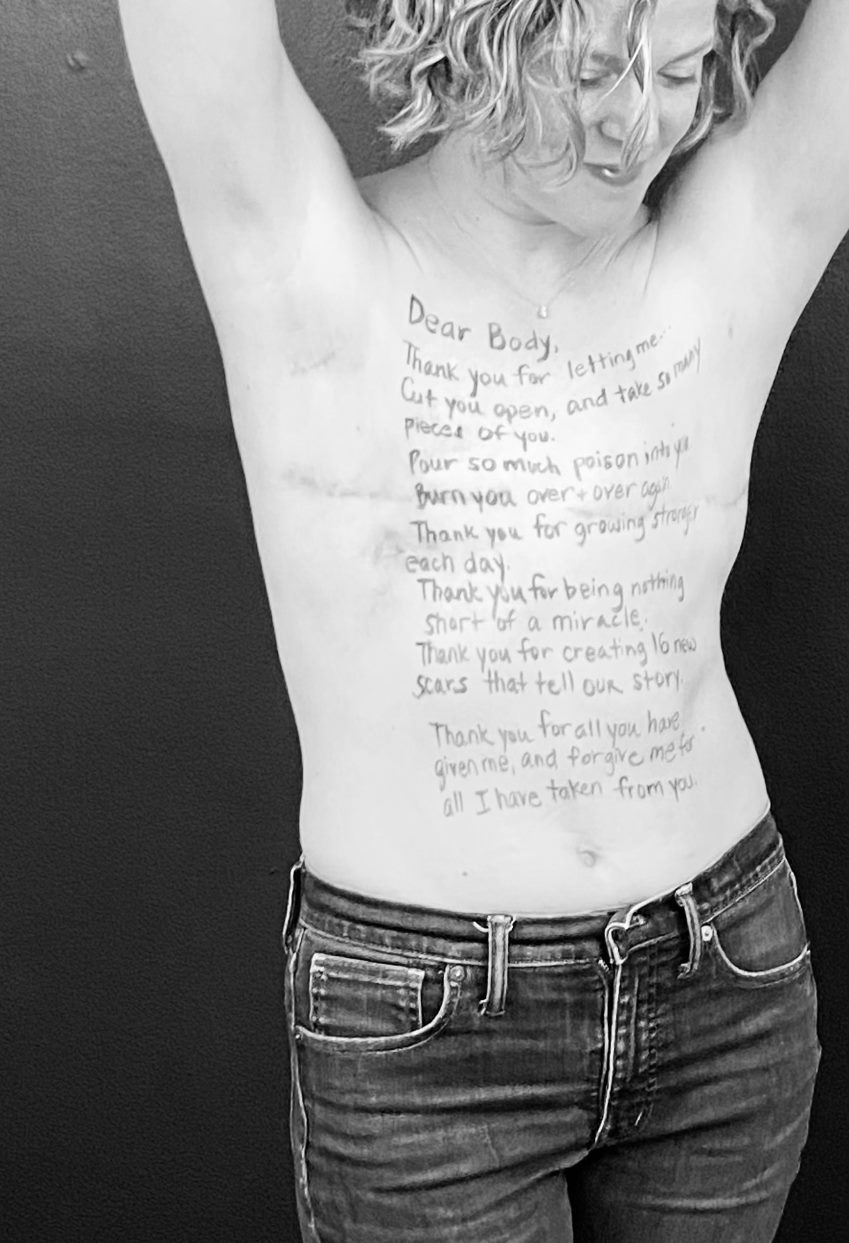

During her experiences that followed – surgeries, chemotherapy, radiation, hormonal therapy, reconstruction, deconstruction (removing implants), parenting and working with cancer – she met other women who were going through similar burdens. She learned many of them didn’t have the supports she did: emotional or physical help from family and friends, financial stability, and access to resources.

At one point, she read an online post from a newly-diagnosed woman who had recently moved to Miami-Dade County, where Rosemary and her family live. The woman was looking for organizations that could help with childcare and housekeeping during treatment. Together, she and Rosemary searched but couldn’t find local groups offering care-related aid. Few national programs exist, they discovered, and those that do offer only limited services in the sprawling Miami area. What’s more, in a county where about 72 percent of residents are Hispanic/Latino, little help was available for Spanish speakers.

“We said, ‘We should do something about this,’” Rosemary recalls, speaking of herself, her sister, and a small group of mentors and friends. By 2020, they had created a local organization to help. They called it the 305 Pink Pack, named for Miami-Dade’s main telephone area code.

Breaking silence

Before the 305 Pink Pack came into existence, Rosemary had her own story of breast cancer-related difficulties and challenges. Growing up in a Cuban American family, talk of cancer “was always very hush-hush,” she says. When someone died of cancer, family members were secretive about cause of death. That lack of information complicated Rosemary’s efforts to learn if genetics affected her diagnosis. Testing eventually showed she had no genetic markers for breast cancer.

At first, Rosemary told only her parents, her husband, and her sister about her diagnosis. She avoided telling her grandmother and extended family until she had learned enough to make a treatment plan and set a surgery date. That helped her avoid unwanted questions or opinions.

These days, she tells her story easily and encourages others to share their own. “It’s important to talk about these things and make it a normal conversation to have, so we’re aware that breast cancer can happen at 40 or younger—and it’s important to get checked,” she says.

Changing reconstruction plan

Rosemary’s story includes a double mastectomy, with expanders put in during surgery and much chest pain afterwards. She was told the pain would be “greatly relieved” when the expanders were replaced by breast implants. “I expected all the pain I was having to improve,” she says. “It actually kept worsening with time.”

That chronic pain interfered with daily life. It kept her from walking down the block where she lived. She spent most days lying down or sleeping. “My daughter was three years old at this point, and I couldn’t participate in anything she was doing.”

When Rosemary needed surgery to fix the lopsided appearance of her breasts caused by radiation, she thought about having the implants removed to stop the pain. She went to a different plastic surgeon to ask about going flat.

“She terrified me,” Rosemary recalls. “The first thing she said was, ‘Are you married? Because no man is gonna want you without breasts.’” That doctor showed her photos of women who had gone flat and said that Rosemary would be “more deformed” than they were because she had been treated with radiation.

After that, Rosemary worried about telling her original plastic surgeon that she wanted to go flat. To her surprise, he was supportive and said he would remove the implants but couldn’t guarantee her pain would be gone. The chest pain and pulling she felt would be alleviated, he added, but pain might remain from previous surgeries and radiation.

Rosemary had the implants removed in December 2020. “I felt better within 72 hours. It was incredible the difference in my levels of activity and function,” she says.

Since the removal, other treatment-related side effects are mostly gone. These include arm lymphedema and joint pain she had attributed to taking an aromatase inhibitor, Anastrozole, which she still takes. In October 2022, Rosemary ran her first marathon.

Some of her family culture about cancer persists. “I will be very open about my whole experience, which shocks my grandmother. She does not do well with how open I am about it,” she says.

When Rosemary wears tight tops, her grandmother asks if she would be more comfortable wearing her prosthetic breasts underneath. “My flatness is hard for her,” she says. Her grandmother also objected to her running in the marathon because she believes it’s not healthy to do after treatment.

Yet most family members have supported Rosemary’s decision to go flat. “Everyone saw how much in pain I was,” she says. “They were just happy to see me feeling normal again. It was a significant difference.”

Giving help to others

When Rosemary was in treatment, her younger sister Nathalie coordinated friends and family to make meals, watch the baby, and meet other life needs. As a result, the 305 Pink Pack’s guiding philosophy became to “be a Nathalie” to any woman in Miami-Dade with a cancer diagnosis.

The group provides free direct support services, such as transportation, childcare, housekeeping, self-care, food help, and oncology massage, with no financial status requirement. A new project, the Power of Hair, provides wigs that match hair types for women of color. The Pack identified that need because most existing programs don’t have such wigs, and “many women want wigs that look like them,” Rosemary says.

Those receiving services range in age from 27 to 89, with 40 percent younger than 50 years old. Women with early-stage cancer receive free services for 12 weeks. Women with metastatic cancer receive a stipend to use anytime during treatment. Most are referred by social workers at local treatment centers.

Help is offered in Spanish and English. Cultural understanding has shaped better support. “There’s a very big difference in how women view support programs in the Latin culture,” says Rosemary, explaining that many don’t want to discuss personal issues in group settings. The Pack holds some activities that are not centered on having cancer, which encourages making support connections more naturally.

The group focuses its advocacy efforts on helping Miami-Dade women advocate for themselves to get the care they deserve.

“We’re making the conversation about breast cancer more comfortable and bringing more awareness to how much of a disproportion there is in the Latino and Black communities as far as the results of breast cancer treatment,” Rosemary says.

“We want to make a dent locally and then, hopefully, that advocacy will keep moving from there.”

This article was supported by the Grant or Cooperative Agreement Number 1 U58DP006672, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Stay connected

Sign up to receive emotional support, medical insight, personal stories, and more, delivered to your inbox weekly.